I stood waiting impatiently for my turn to swing from the rope and drop down into the cool water below. The swimming hole hidden in the Catskill Mountains was a delicious diversion on a warm summer day for those of us lucky enough to have discovered it.

When my turn came, I grabbed the rope, and swung out far over the water.

My timing must have been off, because instead of dropping in the center of the hole, I landed on the steep sides of the canyon where the water was only a few feet deep.

I gasped, momentarily paralyzed by a sharp stabbing pain in my spine. Another diver helped me out of the water and ran to the nearest house to call an ambulance; there were no cell phones back in 1977. There were also no roads to our remote swimming hole, and I remember the EMTs carrying me down the steep mountain path on a stretcher.

I was lucky (and young); my compression fracture healed within a few months and the accident receded into the past. But ten years later, newly married and living in New York, my pain mysteriously resurfaced. Eventually, it became so intense that I had to write on my back lying on a heating pad.

“It’s in the exact place where I broke my back,” I said to my husband, John. “The old injury must be acting up.”

John knew of a celebrity chiropractor renowned for treating Broadway dancers. Surely he would know about back pain.

Dr. Pressman (aptly named) manipulated my back and employed ultrasound and massage. When these failed to help, he recommended limiting physical activity.

“Most importantly,” he cautioned, “do not under any circumstances do the breaststroke.” ( I swam regularly at the Midtown YMCA.) “The breaststroke puts extra strain on the lower back.”

The breaststroke was the most pleasurable and relaxing swimming stroke, and I couldn’t resist sneaking in a few laps now and then. But each time I did, I emerged from the pool crippled with pain.

And then things got worse. My back pain got so bad I could barely walk, which was a serious problem living in a fifth-floor walkup. Dr. Pressman prescribed a tight-fitting corset similar to the one I had worn after my back accident. Now, not only was my physical activity circumscribed, but my very breath was constricted.

I was terrified; my world seemed to be shrinking.

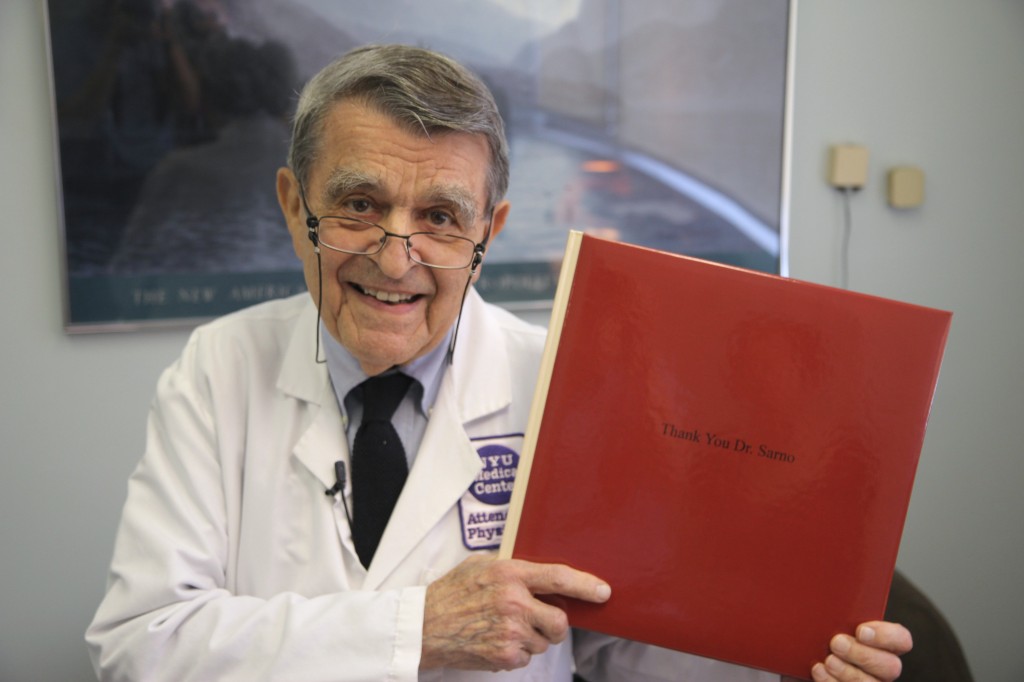

Until he died at the age of 93, Dr. John E. Sarno revolutionized the field of psychosomatic disorders.

About this time a friend showed me an article she’d read in New York Magazine by Tony Schwartz, who described a year spent in inexorable back pain. He had visited many doctors and alternative practitioners and tried every conceivable cure but nothing relieved his pain – until he consulted Dr. John Sarno, a professor of Rehabilitation Medicine at New York University School of Medicine.

Without fully understanding what magic Dr. Sarno evoked, I hurried out and bought his book, Mind Over Back Pain. I was barely half-way through when something that did seem magical, or at least miraculous, happened.

All trace of my back pain completely vanished.

“I can’t believe it!” I told anyone who would listen, “Dr. Sarno’s book cured my back pain!”

Just to be thorough, I followed up with a visit to the doctor himself.

When I met him, Dr. Sarno appeared friendly and business-like in an immaculate white lab coat and tie, a stethoscope around his neck.

“There’s absolutely nothing wrong with your back,” he said, after examining my X-rays.”

“But what about the old injury?” I asked.

“It’s healed, and in any case it’s not causing you any pain.”

Dr. Sarno educated his patients to understand that most chronic pain is an attempt to distract from unconscious painful emotions, such as rage or grief. He believed the physical symptoms resulted from a muscle spasm which sets in motion a self-perpetuating cycle of fear and pain. Dr. Sarno named this condition “tension myositis syndrome,” (TMS), also known as “mind-body syndrome.”

Dr. Sarno’s is a knowledge cure; you do not have to understand the unconscious emotions to relieve the symptoms, except in rare cases where the repressed emotional pain is intolerable. In that case therapy may be a necessary adjunct.

It is understandable that we develop physical symptoms to mask feelings that are socially or psychologically unacceptable. No one wants to reply a casual “How are you?” with “I’m fine except for the rage over being invisible to my parents,” or “I’m great except for the grief over my father’s death.” It’s easier to tell others (and yourself) “My bad knee (hip, shoulder, neck) is acting up again.” Indeed, one of the unconscious mind’s favorite tricks is to create pain at an old injury site (as with my back pain) in an attempt to convince you this symptom is not brain-generated.

In his last book, The Divided Mind: The Epidemic of Mind-body Disorders, Dr. Sarno wrote about his successful treatment of thousands of patients not only for back pain but other conditions, such fibromyalgia, heartburn, joint pain, and chronic fatigue. TMS also manifests psychologically as phobia, depression, or anxiety. Paradoxically, by creating symptoms, the unconscious mind is trying to protect you from a deluge of powerful repressed emotions.

Other physicians and practitioners, too, are discovering the psychological basis of somatic illness. In her book Is It All in Your Head?: True Stories of Imaginary Illness, British neurologist, Suzanne O’Sullivan, M.D. states that approximately a third of her patients experience psychosomatic seizures. The Pain Psychology Clinic in California has over twenty practitioners, while Curable: The App for Chronic Pain allows you to work at your own pace, at home. Filmmaker Michal Galinsky’s movie, All the Rage, Saved by Sarno, (2016), documents Dr. Sarno’s lifelong crusade against the billion-dollar chronic pain epidemic. The film chronicles Dr. Sarno’s successful treatment of prominent figures, including John Stossel, Larry David, and Howard Stern.

Of course it’s important be examined by your doctor to rule out serious illness or rare structural conditions that can cause pain. (Dr. Sarno later declined to treat my husband when he suffered from an internal bleed that destroyed the nerves of his leg; knowledge was not going to resolve that.)

Although my back pain vanished after consulting Dr. Sarno, my unconscious mind did not appreciate being called out. As soon as I accepted that the cause of my pain was TMS-related, I created a new symptom to take its place. Dr. Sarno called this the symptom imperative. People who exhibit the typical TMS temperament – driven, ambitious, perfectionistic – are especially susceptible.

“OK guys, she’s on to us with the back pain,“ I imagined my unconscious mind saying. “Let’s give her knee pain or irritable bowel or painful bladder or anything to distract her from repressed emotions and convince her this is not psychosomatic.”

As much as I want to spread the good news about Dr. Sarno, I am hesitant to tell people in chronic pain about TMS.

“How can you say it’s all in my head?” they argue. “I’m not crazy! The pain is real.”

“I saw my x-rays! My doctor says I have a herniated disc” (or a bone spur or arthritis).

As Dr. Sarno discovered, these physical conditions do not necessarily result in pain. In The Divided Mind, he describes a patient whose orthopedist recommended surgery after the patient’s x-ray showed substantial degeneration of his left hip. After this recommendation, his left hip pain increased . . . When he told me that his right hip felt fine, I asked him to humor me by having both of his hips ex-rayed. On x-ray both hips had the same “degenerative” change, yet his right hip did not hurt!”

As I was leaving Dr. Sarno’s office that day in back 1987, I stopped and turned around. “Dr. Sarno,” I asked, “can I do the breaststroke?”

“Not only can you do the breaststroke,” Dr. Sarno said, raising a finger in the air for emphasis, “if you want to get better, you must do the breaststroke.”

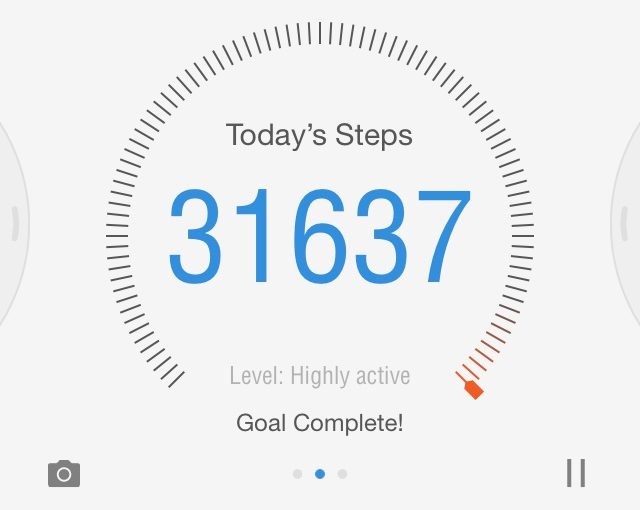

After that I did lap after lap of the breaststroke, kicking as hard as I could and never experienced a tinge of back pain. Although I still experience the symptom imperative to some extent, Dr. Sarno’s discoveries have dramatically decreased the intensity and duration of these episodes, and given me a rich and enduring appreciation for the power of the mind.

As hundreds of thousands of grateful patients have said before me, thank you, Dr. Sarno.

Note: This essay was originally published in Folks at Pillpack, which is no longer in print. All right to this piece have reverted to me.

Pamela J is an author of over thirty children’s books, and an essayist whose work has appeared in The NY Times, The Wall Street Journal, The NY Daily News, Writer’s Digest, The Independent, and The Writer. Pamela has also published humor in The Daily Drunk, Erma Bombeck, Brevity, The Satirist, and others.